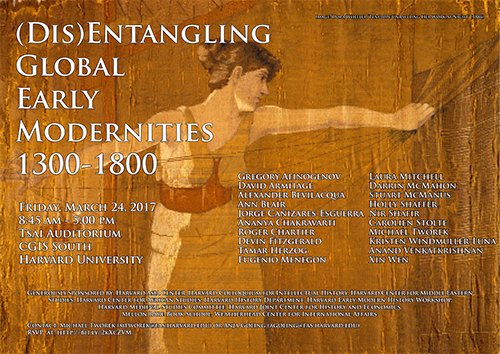

(Dis)Entangling Global Early Modernities, 1300-1800 (24 March 2017)

There are conferences with impressive line-ups, and then there are conferences with very impressive line-ups. The Harvard conference on (Dis)Entangling Global Early Modernities certainly fell in the latter category, as it included several of the most renowned early modernists. Being organized by Michael Tworek (Harvard), Stuart McManus (University of Chicago), Devin Fitzgerald (Harvard) and Anja-Silvia Goeing (University of Zurich), this was indeed one of the most anticipated conferences of the spring semester.

Beyond the scholars involved, the topic itself was considered extremely timely – as is currently the case with many conferences involving global history. Although planning for the conference had started more than a year ago, Professor Tworek explained in his introductory remarks that the political changes in the UK and in the US had already led to arguments about the ‘death’ or ‘demise’ of global history. And if commentators had not yet placed it on its deathbed, then they at least asserted that global historians will need to change their overall approach. In their opinion, too many historians have namely overlooked the costs of (early modern) globalization and ignored those whom it left behind.

In this regard, the conference promised to evaluate the heuristic device of ‘disentanglement’. Explained in brief, this notion is aimed at better understanding the connections within early modern globalization. Again in the view of Professor Tworek, the early modern world pivoted towards integration but contained many incomplete patterns and loose threads. Disentanglement is anticipated to pull at these threads, which in turn would allow us to see where and how they connect with the wider fabric of early modernity. As such, Tworek hoped that the conference would deal with both integration and disintegration, connection and disconnection, and entanglement and disentanglement.

In order to do so, the conference worked around three central topics. The first panel focused on (dis)entangling ideas in early modern globalization and included presentations by Xin Wen (Harvard), Anand Venkatkrishnan (Oxford) and Michael Tworek himself. It also included interventions by Tamar Herzog (Harvard) and Carolien Stolte (Leiden). The second session zoomed in on book history and its relation to globalization with the facilitators here being Ann Blair and Alexander Bevilacqua (both Harvard), and the presenters Holly Shaffer (Darthmouth), Nir Shafir (University of California) and Devin Fitzgerald. Finally, session three discussed scholarly practices and included contributions from Darrin McMahon (Darthmouth), Ananya Chakravarti (Georgetown), Kirsten Windmuller-Luna (Princeton), Stuart McManus and Gregory Afinogenov (Harvard).

Most anticipated was however the concluding roundtable debate, which featured amongst others David Armitage (Harvard) and Roger Cartier (Collège de France). The discussion, held barely two months after the inauguration of President Trump, quickly turned towards the role historians have in analyzing globalization both in the past and in the present. The roundtable also assessed how the increased hostility towards migration and cross-border connections might affect the field itself. Some argued that disentangling globalization will not be enough because it is part of set of familiar historiographies, one that has eventually aided populists to gain power. Others contended that disentanglement is needed because global history has still not been able to escape its originally Eurocentric framework.

To illustrate the dominance of contemporary events even further, during the Q&A session with the roundtable panel, no less than four questions (about one-third of the discussion) pondered directly about the relation between politics and history. In response, virtually all panelists agreed that every history is political, but very few agreed on what that means with regard to the way forward. Some seemed to take the direction that more of the ‘standard’ narratives of global history are needed to oppose populism; others stated that global history should look more towards the ruptures created by globalization itself. Still others felt that historians should pursue first and foremost their own interests, as this more detached research will provide society with a stronger basis to deal with its own past.

Eventually, and despite the political controversies, the conference ended with an appraisal of the notion of disentanglement itself. Most of the participants were in agreement that historians need to look both at what connects and what disconnects. But as a very final question, one senior professor in the audience asked a poignant question: if historians look at what was entangled in the early modern world, does that not automatically mean that they also get a view of what was disentangled? And, in an even more direct question, the same professor asked if the organizers would have selected different participants if the conference had been called simply ‘Entangling Global Early Modernities’?

Beyond the great line-up, this final question was indeed at the core of a greatly inspiring conference: at what point and for what reason do we change the name of what we as historians are doing, and do changes such as going from entanglement to disentanglement really influence the core of our work?

In any case, feel free to judge for yourself: the opening remarks on disentanglement can now be found online and are open for discussion.